Use the Universal Business Analysis Planning Checklist as You Plan Your Business Analysis Approach.

Every project is a unique, temporary endeavor.

The business process management, regulatory compliance and digital transformation projects that business analysts may play a role in all come with different goals, scopes, teams, timelines, budgets dependencies and risks. Though many projects follow similar methodologies they are all tailored for project scope constraints and to take advantage of available resources, opportunities and lessons learned from prior work.

Each business analyst also comes with a unique set of skills and experiences. Almost all business analysts have great communications skills and at least some experience-based business domain knowledge. That’s why they became business analysts in the first place. Every business analyst has uniquely acquired knowledge of business analysis techniques and business domains through personal study, practice and experience. Many have also been trained in elicitation, requirements management, modeling, measurement, analysis and documentation techniques. An ever-growing number have received professional certifications, such as the IIBA Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP) or the PMI Professional in Business Analysis (PMI-PBA).

What is Business Analysis Planning?

The most skilled business analysts are not only competent in many business analysis techniques but also consciously tailor their business analysis approach for each project that they engage in. They have learned to consider key project dynamics along with their own competencies and to tailor their planned business activities and deliverables to suit each project’s unique dynamics. Regardless of your own level of business analysis experience, maturity, and whether you are formally trained, certified or not, you can still consciously assess each project’s dynamics and tailor your forthcoming business analysis work to get the most productivity and value out of your business analysis efforts in each project.

The most significant project dynamics include:

- The methodology, or sequence of stages or major milestones, and the business analysis products or outcomes that are expected by the end of each stage/milestone (and before starting the next).

- The budget and schedule, not only to meet them, but to take advantage of contingency or schedule slack opportunities, to increase the value, quality or to learn.

- The key project stakeholders and relationships that are new and changed and forming, to take a proactive role in fostering and building relationships with and among that team.

- The types and combinations of elicitation techniques that will be best suited for producing or validating business analysis deliverables.

- The business domain knowledge and experiences of the diverse key project stakeholders, including your own unique set of business analysis competencies.

The Universal Business Analysis Planning Checklist

You can be more effective in planning your business analysis approach if you follow a consistent, clear agenda that considers the common project dynamics.

The Universal Business Analysis Approach Planning Checklist covers the most common project dynamics. You can use this as an agenda to elicit and discover a comprehensive view of a project’s key dynamics, its opportunities and use what you discover to adapt/tailor your business analysis approach.

As an exercise, think of a project that you have recently worked on, you are currently working on, or will soon be working on. Answer questions in the following checklist for yourself.

Project Life Cycle

- What are the planned stages of this project?

- What stage are we currently in?

- What is the business analysis deliverable (or set of deliverables) that I am responsible for producing in this stage?

- What is the intended use of my business analysis deliverable(s) and who will use it?

Schedule and Effort Budget

- How much effort can I spend and by what target date am I expected to produce my business analysis deliverable(s)?

- Is that about what I also estimate it will take?

- Is either my effort or date estimate higher than the effort budget or target date? If so, how might I adapt my effort, scope, activities or configuration of my deliverable(s)?

Project Stakeholders and Relationships

- What are the key roles is on the project team and who is in them?

- Does this project have an executive sponsor, project owner or product owner, project manager, specialists and business subject matter experts?

- What are the names and titles the persons in these project roles?

- Are significantly new relationships being are created in this project?

- Who’s new to each other on this team?

- Are there local and who’s remote team members?

- What are peoples’ responsibilities?

- Who is responsible for producing, accepting or needs to be consulted or informed of each of the project’s key deliverables, particularly the business analysis deliverable(s)?

Elicitation Techniques

- Which elicitation techniques are available to me use?

- Documentation Reviews – What documentation or prior work products are available to review?

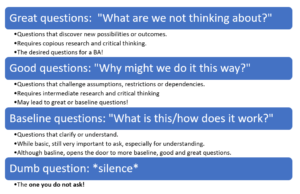

- Interviews and Workshops – Who can I interview or include in a workshop, and what questions would I need to ask?

- Observations – Where and what kinds of observations may be needed and how could I arrange for them?

- System reviews – What system(s) are available to review and for what information?

- Surveys – Who could I engage in a survey and using what types of questions?

- What are my own business analysis competencies?

- Considering this project’s stakeholders and relationships, the elicitation techniques available to me, and my own core competencies, which elicitation techniques are best suited gather and validate my business analysis information?

Organizational Assets

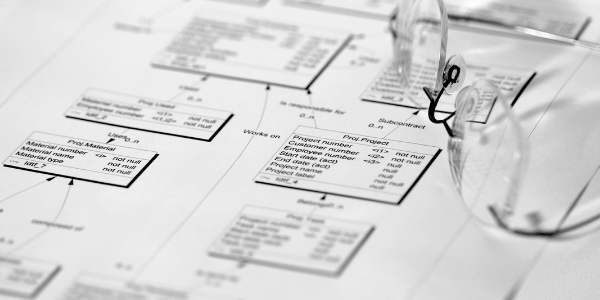

- What specialized tools for elicitation, documentation and modeling are available to me?

- Collaboration tools, facilities, survey tools?

- Diagramming or modeling software?

- What prior business analysis work (e.g., documents, models) that I can draw from?

- Does my organization offer training in the subject business domain?

Competencies and Knowledge

- Who on the project team has what expert business domain knowledge?

- What is my own business domain knowledge?

- What are my strongest core business analysis competencies?

- Where can you take advantage the team’s diversity of knowledge and competencies?

- Who are the best stakeholders in this project to engage in elicitation of content or validation of business analysis deliverables and what is or are the best elicitation techniques to use?

On reflection, are you able to answer these questions for yourself? When you go into your project workplace, who will you include in this conversation?

Conclusion:

Business analysis planning is a recognized business analysis activity. The IIBA Body of Knowledge (BoK) includes the Plan Business Analysis Approach activity within its Business Analysis Planning and Management process. The BoK also lays out the scope of what should be covered by a Business Analysis Approach as “The set of processes, templates, and activities that will be used to perform business analysis in a specific context.”

The time and formality that you apply to business analysis planning is up to you. At the financial institution where I work as a project and program manager, our business analysts typically tailor and document a business analysis plan for each new project to which they are assigned.

I think of business analysis planning as a form of insurance. Spend a little time upfront to assure that the bulk of the rest of your business analysis efforts will be as well spent and effective as possible. Expect the benefits of tailoring a business analysis plan for every project to be that:

- It will help you to align your own core business analysis competencies to each project, and

- You and the project will gain the most value from your business analysis efforts.

That’s a value-adding proposition.

You are welcome to contribute comments about project dynamics that impact business analysis plans or about the checklist presented through the Contact Us page at www.ProcessModelingAdvisor.com.