Projects play an essential role in the growth and survival of organizations today. It is through projects that we create value in the form of improved business processes and new products and services in response to changes in the business environment. Since data and information are the lifeblood of virtually all business practices, projects with significant IT components are often the key mechanism used to turn an organization’s vision and strategy into reality. Executives have their eye on the project portfolio to ensure that they: (1) invest in the right mix of projects, (2) optimize their resources, (3) develop expert capabilities to deliver flawlessly, and ultimately, (4) capture the expected added value to the business. In the 21st century we are bombarded with constant change brought about by the Internet, the global economy and the prevalent use of technology. As a result, there appears to be a never-ending demand for new business solutions supported by IT products and services. Executives across the spectrum are adopting the practices of superior project management and business analysis to increase the value projects bring to their organizations.

The Project Performance Partnership

In the spirit of high-performing teams, project managers align themselves with professional business analysts, expert technologists, and business visionaries to understand business problems or new opportunities, and determine the most appropriate, cost-effective, fastest time to market, and innovative solutions. As this core team forms, a project performance partnership emerges that rivals the world’s great teams, (e.g., tiger teams, special operations teams, professional sports teams, parametric teams). At the center of the team is the dynamic twosome: the project manager and the business analyst. The project manager keeps an eye on the management of the project, ensuring the project delivers on time, on budget and with the full scope of the requirements met. While the business analyst focuses on management of the business need, business requirements, and expected business benefits. The wise project manager welcomes this teaming trend, understanding that inadequate information relating to business needs leads to poor estimates, and makes time and cost management virtually impossible.

Business analysis and project management have become central business management competencies of the 21st century. These competencies are essential because requirements play a vital role in engineering business solutions, and projects are essential to organizational success. In addition, organizations are realizing that the reasons projects fail are almost always tied to poor requirements and ineffective project management. (The Standish Group International, 1994-2006). The table below depicts the resolution of 30,000 applications projects in large, medium, and small cross-industry U.S. companies tested by the Standish Group from 1994 to 2006.13

|

Year

|

Successful Projects

|

Failed Projects

|

Challenged Projects

|

|

2006

|

35%

|

19%

|

46%

|

|

2004

|

29%

|

18%

|

53%

|

|

2000

|

28%

|

23%

|

49%

|

|

1998

|

26%

|

28%

|

44%

|

|

1996

|

27%

|

40%

|

33%

|

|

1994

|

16%

|

31%

|

53%

|

Source: The Standish Group Project Resolution History, CHAOS Research Reports (1994–2006)

Clearly there has been a steady improvement in project performance since 1994. According to the Standish reports, the reasons for the overall improvement include: smaller projects (the average cost of a project had been downsized more than half by 2001); better skilled project managers; and better methods and tools to manage changes. The Standish Group continues to recommend minimizing project scope, reducing project resources, and downsizing timelines to improve project success. The Standish Group also predicts that the number of critical projects wills double each year; therefore, we must continue to work vigilantly to improve project performance, paying particular attention to the elements it calls the Recipe for Project Success: The CHAOS Ten, which are listed here grouped by category. Notice that many of these elements relate to business analysis and the remaining are about better project management.

Recipe for Project Success: The CHAOS Ten

|

Project Management

|

Business Analysis

|

- Executive support

- Experienced project managers

- Standard infrastructure

- Formal methodology

- Reliable estimates

- Small milestones, proper planning, and competent staff

|

- User involvement

- Clear business objectives

- Minimized scope

- Firm basic requirements

|

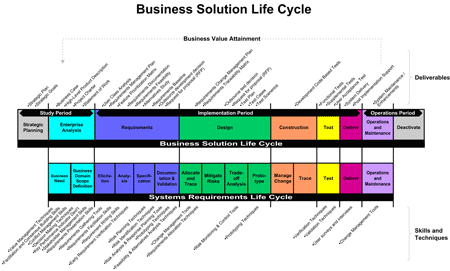

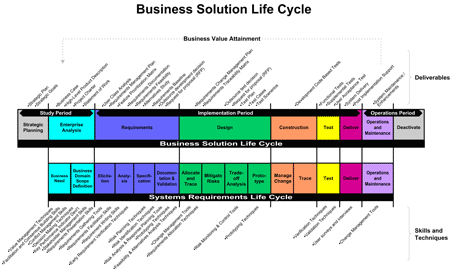

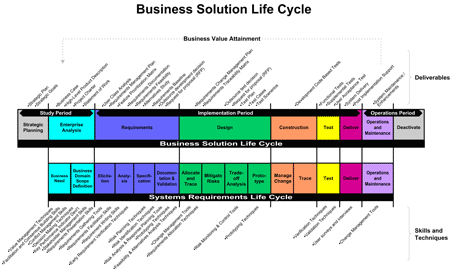

It is the project manager who owns the Business Solution Life Cycle, and the business analyst who owns the Systems Requirements Life Cycle, from understanding the business need to ensuring that the delivered solution meets the need and adds value to the bottom line. (See Figure 1, below) For complex 21st century projects, the business analyst has a critical role throughout the Business Solution Development Life Cycle, not simply during the requirements phase. Business requirements analysis differs from traditional information systems analysis because of its focus, which is exclusively on adding value to the business. In particular, project managers rely on business analysts to assist in providing more detailed project objectives; business needs analysis; clear, structured, useable requirements; trade-off analysis; requirement feasibility and risk analysis; and cost-benefit analysis. Poor requirements definition emerges without this key liaison between business and IT departments, resulting in a disconnect between what IT builds and what the business needs.

Figure 1 – Business Solutions Life Cycle Mapped to the Systems Requirement Life Cycle

Combining Disciplines Leads To Success

For organizations to achieve strategies through projects, a strong partnership between the project manager and the business analyst is essential. Indeed, when this partnership exists, and they both embrace the contributions of expert technologists and business visionaries, collaboration, innovation and far superior project performance is realized. For an in-depth discussion of the project manager and business analyst partnership, it is helpful to frame the dialogue in the context of a generic project cycle. Refer to Figure 1 once again, the Business Solution Life Cycle Mapped to the Systems Requirements Life Cycle, to provide context as we examine the nature of the partnership. The diagram shows a sequential development approach, from strategic planning to the business requirements to the delivery of a complete business solution. This is a simplistic model that guides the development process through its typical phases.

Strategic Planning and Enterprise Analysis

Strategic Planning

Strategic planning is the first phase in the Business Solution Life Cycle. During this phase the current state of an enterprise is examined and the desired future state is determined and described by a set of broad goals. The goals are then converted to measurable objectives designed to achieve the strategy.

Project managers and business analysts may not contribute directly to strategic planning activities since it is the responsibility of the senior leadership team. However, senior business analysts and project managers may be asked to conduct market research, benchmark studies or competitive analysis surveys to inform the executive team as input to the strategic planning process. In some organizations, senior business analysts and project managers help plan and facilitate strategic planning sessions. Nevertheless, business analysts and project managers should have a full understanding of the strategic direction of the enterprise to determine how new initiatives fit into the long term strategy and/or mission of the organization, and to help build and manage the business case and other relevant information regarding business opportunities.

Enterprise Analysis

The enterprise analysis phase of the Business Solution Life Cycle consists of the collection of activities for depicting the current and future views of the business to determine the gap in organizational capabilities needed to achieve the business strategies. Enterprise analysis activities then determine new business opportunities to close the gaps.

Enterprise analysis activities begin after the executive team of the organization develops strategic plans and goals. The core activities center on: (1) identifying new business opportunities or solutions to business problems, (2) conducting studies, gathering information and determining the solution approach, (3) developing a business case or project proposal document to recommend a new project to the leadership team for their decision whether to select, prioritize and fund a new project. If the new change initiative is selected, a new project is formed and requirements elicitation and project planning commence.

Deliverables

The business analyst and project manager collaborate with selected business and technology experts to produce the deliverables of the enterprise analysis activities.

|

Deliverables

|

Description

|

|

Business Architecture

|

The business architecture is the set of artifacts that comprise the documentation about the business.

|

|

Feasibility, Benchmark, Competitive Studies

|

Conducting formal or informal studies prior to proposing a new project helps to discover very important information about the business opportunity.

|

|

New Business Opportunities

|

As an outgrowth of strategic planning, the business analyst and project manager review the results of feasibility, benchmark and competitive analysis studies, and the target business architecture to identify potential solution alternatives to achieve strategic goals.

|

|

Business Case

|

A business case should be developed for all significant change initiatives and capital projects.

|

|

Initial Risk Assessment

|

Once the business case is developed, the project manager and business analyst facilitate a risk management session using the same set of experts.

|

PM/BA Collaboration Opportunities

The project manager and business analyst have numerous opportunities for collaboration to complete the enterprise analysis activities, including:

- Conducting feasibility, benchmark and competitive studies

- Creating the business case, scope statements, preliminary time and cost estimates

- Conducting risk assessment and risk response planning

- Establishing project priorities

- Managing stakeholders

- Getting the right people involved and excited about the potential project

- Partnering with senior IT architecture team to create the solution’s “vision”

Requirements and Design

During the requirements and early design phases the business need is discovered, analyzed, documented and validated and the solution concept begins to come into view.

Requirements Elicitation

Requirements are always unclear at the beginning of a project. It is through the process of progressive elaboration that requirements evolve into maturity. Requirements elicitation involves conducting initial requirements gathering sessions with customers, users, and stakeholders to begin the specification process. Requirements gathering techniques include: discovery sessions and workshops, interviews, surveys, prototyping, review of existing system and business documents, and note taking and feedback loops to customers, users, and stakeholders.

Requirements Analysis

Requirements are first stated in simple terms, and are then analyzed and decomposed for clarity. Requirements analysis is the process of structuring requirements information into various categories, evaluating requirements for selected qualities, representing requirements in different forms, deriving detailed requirements from high-level requirements, and negotiating priorities. Requirements analysis also includes the activities to determine required function and performance characteristics, the context of implementation, stakeholder constraints, measures of effectiveness, and validation criteria. Through the analysis process, requirements are decomposed and captured in a combination of textual and graphical formats. Analysis activities include:

- Studying requirements feasibility to determine if the requirement is viable technically, operationally, and economically

- Trading off requirements to determine the most feasible requirement alternatives

- Assessing requirements feasibility by analyzingrequirement risks and constraints and modifying requirements to mitigate identified risks. The goal is to reduce requirement risks through early validation prototyping techniques

- Modeling requirements to restate and clarify them. Modeling is accomplished at the appropriate usage, process, or detailed structural level

- Deriving additional requirements as more is learned about the business need

- Prioritizing requirements to reflect the fact that not all requirements are of equal value to the business. Prioritization may be delineated in terms of critical, high, average, and low priority. Prioritization is essential to determine the level of effort, budget, and time required to provide the highest priority functionality first. Then, perhaps, lower priority needs can be addressed in a later release of the system.

Requirements Specification

Requirement specifications are elaborated from and linked to the structured requirements, providing a repository of requirements with a completed attribute set. Through this process of progressive elaboration, the requirements team often detects areas that are not defined in sufficient detail, which, unless addressed, can lead to uncontrolled changes to requirements. Specification activities involve identifying all the precise attributes of each requirement. The system specification document or database is an output of the requirements analysis process.

Requirements Documentation

Requirements documentation must be clear and concise since it is used by virtually everyone in the project. Transforming graphical requirements into textual form can make them more understandable to non-technical members of the team. Documentation activities involve translating the collective requirements into written requirements specifications and models in terms that are understood by all stakeholders.

Requirements Validation

Requirements validation is the process of evaluating requirement documents, models, and attributes to determine whether they satisfy the business needs and are complete enough that the project team can commence work on solution design and construction. The set of requirements is compared to the original initiating documents (business case, project charter, statement of work) to ensure completeness. Beyond establishing completeness, validation activities include evaluating requirements to ensure that design risks associated with the requirements are minimized before further investment is made in solution development.

Deliverables

The business analyst and project manager collaborate with selected business and technology experts to produce the requirement deliverables:

|

Deliverables

|

Description

|

|

Stakeholder analysis and communication needs

|

Interviews are conducted with individuals and small groups to find out what business functions must be supported by the new solution.

|

|

Elicitation Workshops

|

Requirements workshops are an efficient way to gather information about the business need from a diverse group of stakeholders.

|

|

Surveys

|

Surveys can provide a valuable tool to collect a large amount of information from an array of stakeholders efficiently and quickly.

|

|

Document Reviews

|

The business analyst and project manager review all existing documentation about the business system, including policies, rules, procedures, regulations, process descriptions.

|

|

Test Plan

|

Typically a document that describes the scope, approach, resources and timing of test activities.

|

|

Business Requirements Documentation and Validation

|

Structured, validated, archived and accessible requirements are the functional and performance needs for the new solution, captured in: documents, tables and matrices, models, graphics, prototypes

|

|

Requirements Management Plan

|

A document that describes how changes to requirements will be allocated, traced and managed.

|

PM/BA Collaboration Opportunities

The project manager and business analyst have numerous opportunities for collaboration during requirements activities, including:

- Conducting requirements elicitation workshops

- Determining the number of iterations of requirements elicitation, specification, and validation

- Determining the appropriate life cycle choice (e.g., waterfall, Agile, Spiral)

- Developing the project management plan

- Conducting trade off analysis for the requirements and solution trade-offs

- Balancing the competing demands

- Validating requirements

- Prototyping

- Updating the business case

- Planning and facilitating the control gate review, signoff on requirements, and go/no decisions

Solution Construction and Test

During the solution construction and testing, the business analyst and project manager collaborate to ensure changes to requirements are identified, specified, analyzed for impacts to the project (cost, schedule, business value add), and dispositioned appropriately. The goal for both the business analyst and the project manager is to reduce the cost of changes, and welcome changes that add business value. Requirements management activities include: allocating requirements to solution components, tracing requirements throughout system design and development, and managing changes to requirements.

Deliverables

The business analyst and project manager collaborate with selected business and technology experts to produce the deliverables of the solution construction and test activities.

|

Deliverables

|

Description

|

|

Solution Verification and Validation

|

- Validating requirements to provide evidence that the designed solution satisfies the requirements through user involvement in testing, demonstration, and inspection techniques. The final validation step is the user acceptance testing.

- Verifying requirements to provide evidence that the designed solution satisfies the requirements specification through test, inspection, demonstration, and/or analysis.

|

|

Business Policies, Procedures, Rules, Education

|

- For new business solutions, there are almost always changes to business rules, policies, and procedures.

|

|

Testing

|

- Including integration, system, and user acceptance testing.

|

PM/BA Collaboration Opportunities

The project manager and business analyst have numerous opportunities for collaboration during solution construction and testing phases including:

- Developing the test plan and test approach

- Validating activities to ensure the solution meets the business requirements (customer reviews, product demonstrations)

- Reviewing test results and dispositioning identified defects

- Conducting defect root cause analysis and determining the appropriate corrective action

- Managing issues

- Managing stakeholders

- Facilitating the go/no go decision to deliver

Solution Delivery

Planning for the organizational change management that is brought about by the delivery of a new business solution is often partially or even completely overlooked by project teams that are focused mainly on the IT application system. While the technical members of the project team plan and support the implementation of the new application system into the IT environment, the business analyst and project manager are working with the business unit management to bring about the benefits expected from the new business solution by:

- Assessing the organizational readiness for change, and planning and supporting a cultural change program;

- Assessing the current state of the knowledge and skills resident within the business, determining the knowledge and skills needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting the training, retooling and staff acquisition for skill gaps;

- Assessing the current state of the organizational structure within the business domain, determining the organizational structure needed to optimize the new business solution, and planning for and supporting the organizational restructuring;

- Developing and implement a robust communication campaign to support the organizational change initiative; and

- Determining, enlisting and supporting managements’ role in the championing the change.

Deliverables

The business analyst and project manager collaborate with selected business and technology experts to produce the deliverables of the solution deployment activities.

|

Deliverables

|

Description

|

|

Deployment plans

|

Developing and communicating the plans to implement the new business solution. |

|

Business policies, rules, procedures

|

Implementation of business policies, procedures, rules, etc. |

|

Education and training

|

Training of business customers, stakeholders and users to accept and operate the new business solution efficiently. |

|

Post-implementation support

|

The business analyst and project manager provide support to the business customers, stakeholders and users to help them learn how to operate the new business solution efficiently, and to resolve any issues that arise. |

|

Lessons learned

|

The business analyst and project manager conduct lessons learned sessions with the project team, the business customers, stakeholders and users, and the technical team to determine what went well, and what needs improvement for future projects. |

PM/BA Collaboration Opportunities

The project manager and business analyst have numerous opportunities for collaboration during solution deployment activities including:

- Developing, communicating, and getting approval for the deployment plan

- Approach (deploy to all business units or use a phased in)

- Which business units are affected?

- When will the business units be implemented?

- When will training be delivered?

- When will post-implementation support by the core project team end?

- Making the decision to move to O&M

- Conducting lessons learned sessions

Operations and Maintenance

The business analyst and project manager contribution to the success of the project does not end when the business solution is delivered and operational. There are key responsibilities during Operations and Maintenance (O&M) that must be filled. O&M is the phase in which the system is operated and maintained for the benefit of the business. Maintenance services are provided to prevent and correct defects in the business solution.

Deliverables

The business analyst and project manager collaborate with selected business and technology experts to produce the deliverables of the O&M phase.

|

Deliverables

|

Description

|

|

Solution benefits measurement

|

The actual business benefits that are realized are captured, analyzed and communicated. |

|

Identification, prioritization, and planning for solution enhancements

|

Maintenance and enhancements projects are: identified, prioritized by business value, planned, executed |

| Decision to deactivate |

At some point, the solution will need to be replaced. The decision to do so often involves the enterprise analysis activities described above. |

PM/BA Collaboration Opportunities

The project manager and business analyst have numerous opportunities for collaboration during O&M including:

- Prioritization of enhancements

- Root cause analysis of performance and value attainment issues

Final Words

Gaps in technology, techniques, and tools are not the fundamental reasons why projects fail. Rather, project failure most often stems from a lack of leadership and poor choices made by people. Undeniably, the business analyst and project manager are evolving into strategic project leaders of the future. The key issues are no longer centered on control and management, but rather collaboration, consensus, and leadership. Team leaders develop specialized skills that are used to build high-performing teams. When building software-intensive systems, well managed teams undoubtedly accomplish more work in less time than do poorly managed teams (Bechtold, 1999).

References

Bechtold, R. (1999). Essentials of software project management. Vienna, VA: Management Concepts.

Hadden, R. (2003). Leading culture change in your software organization. Vienna, VA: Management Concepts.

Mooz, H., Forsberg, K., & Cotterman, H. (2003). Communicating project management: The integrated vocabulary of project management and systems engineering. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

The Standish Group International, Inc., “2007 First Quarter Research Report,” The Standish Group International, Inc. (2006–2007).

The Standish Group International, Inc., “Extreme CHOAS,” The Standish Group International, Inc. (2001), Online at http://www.smallfootprint.com/Portals/0/Standish%20Group%20-%20Extreme%20Chaos%202001.pdf (accessed January 2008).

Stevens, R., Brook, P., Jackson, K., & Arnold, S. (1998). Systems engineering: Coping with complexity. Indianapolis, IN: Pearson Education, Prentice Hall PTR.

Kathleen B. Hass, PMP

is Senior Practice Consultant for Project Management and Business Analysis, and Director at Large and Chapter Governance Committee chair for the International Institute of Business Analysis (http://www.theiiba.org/). She is the author of Managing Complex Projects: A New Model (Management Concepts, October 2008). Since 1973, Management Concepts, headquartered in Vienna, VA, has been a global provider of training, consulting and publications in leadership and management development. Management Concepts is a Gold International Sponsor and an IIBA Endorsed Education Provider For more information, visit http://www.managementconcepts.com/ or call 703 790-9595.