A First Pass at Defining the BA/PM Position Family

In the previous article I set forth and compared the skills profile of the Business Analyst and the Project Manager. That was a very high level comparison. In order to get down to the practice level proficiency, it is necessary to define the BA/PM Position Family. That is the intent of this article. Recognize that this is my opinion and has not been discussed with any of my business analyst or project manager colleagues.

The responses to the first three articles have been overwhelming. They have been both positive and negative. Being a change management advocate, I am pleased with your reactions. My hope is that we can continue the exchange. As always I welcome opposing positions and the opportunity to engage in public discussions. Your substantive comments are valuable. Criticism is fine and is expected but, in the spirit of agile project management, so are suggestions for improvement.

I realize that I have taken a controversial position and I do so intentionally. At least I have your attention whether you agree with my position or not.

Professional Development of the BA/PM

In the previous article I offered a first pass at defining the BA/PM position family. I see that family as consisting of the following six positions:

-

BA/PM Team Member

- BA/PM Task Manager

- BA/PM Associate Manager

- BA/PM Senior Manager

- BA/PM Program Manager

- BA/PM Director

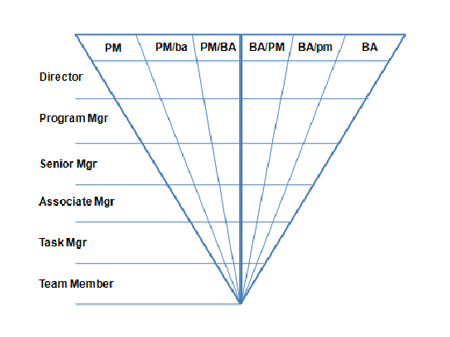

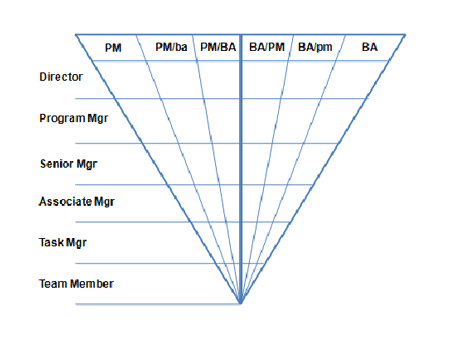

Let me offer the next level of detail for each of these positions. Years ago I had the opportunity to consult with the British Computer Society on the development and implementation of their Professional Development Program. A few years later I had the occasion to develop an internet-based decision support system for IT career development for one of my clients. That system was called CareerAgent. In this article I have integrated that model into the earlier work for the British Computer Society. Much of what I define below takes advantage of the deliverables from both of those engagements. The result is the graphic shown below.

Figure 1: The Project Manager and Business Analyst Landscape

Figure 1 is interpreted as follows. The extreme left and right vertical sectors identify those professionals who are either pure project managers (PM) or pure business analysts (BA) with the accompanying skills and competencies needed for their positions. All of the sectors in between are professionals having some combination of project management and business analyst skills and competencies. For example, as you move from the PM to the PM/ba sector you identify professionals who have pure project manager skills and competencies plus some business analyst skills and competencies. Most project managers would have some business analyst skills and competencies. Project management remains the primary focus of their position. The same interpretation holds for the BA/pm sector. The primary focus of their position is business analysis and many business analysts have some project management skills and competencies. In the middle sectors are the PM/BA and BA/PM professionals. These are the professionals that I have been referring to in all the preceding articles. They are fully qualified to manage projects and manage business analysis engagements. Their skill and competency profiles are equivalent. Their primary orientation is either as a project manager (PM/BA) or as a business analyst (BA/PM). I believe that the major career opportunities are for the PM/BA or BA/PM professionals.

The rows of this landscape refer to the six levels in the position family. At the staff level there are two positions. At the entry level are the Team Members. These professionals will have an entry level skill and competency profile that qualifies them to be a team member in a project (PM) or business analysis (BA) effort. As they gain experience they will move up to the Task Manager level where they will be qualified to supervise the work of a task, perhaps with the support of other team members. At the professional level there are two positions. The lower of the two is the Associate Manager. These positions are qualified to manage small, simple projects. Through experience they progress to the Senior Manager level. They are now qualified to manage even the most complex projects. The Director level positions are of two types. One is the Program Manager. This position is both a consultant-type position as well as a manager of project managers working on a program – a collection of projects having some relationship with one another. The other position is the Director position. These are people management positions. They are the highest level of the six position family.

Using the Landscape for Professional Development

Each cell in the landscape will have a minimum skill and competency profile defined for all positions in that cell. In order for an individual to be in this cell, they must possess the minimum skill and competency profile for the cell that they occupy, or would like to occupy. For professional development planning, the individual will be in some particular cell and have career aspirations to move to another position in the same cell, or to a position in another cell (usually this will be an adjoining cell). The skill and competency profile of the current and desired positions or cells can be compared and the differences will identify the skill and competency gaps. The training and experience needed to remove that gap and be qualified to move to a position in the desired cell can be defined. The implications to the training department planning are obvious, as are the applications to human resource management.

What Might a Professional Development Program Look Like?

This is a big topic. By way of introduction I think that a good professional development program should consist of the four parts briefly defined below

- Experience Acquisition

Further experience mastering the skills and competencies needed in the current position - On the job training

Training to increase the proficiency of skills and competencies needed in the current position - Off the job training

Training to increase the proficiency of skills and competencies needed in the desired position - Professional activities

A combination of reading, professional society involvement, conference attendance and networking with other professionals

Every position in every cell will have a minimum skill and competency profile required for the position. To qualify for a specific position the individual must first define the skill and competency gap between their current and desired position and then build a professional development program using the above four components to remove that gap. That would position the individual to move to the desired position when a vacancy arises. Each individual should have a mentor assigned to them to help with plan development and other career advice.

Putting It All Together

Obviously this is a work in progress. It has been done for the IT profession but not for the BA/PM professional (or PM/BA if you prefer). Much remains to be done. I would certainly like to hear your thoughts on the BA/PM professional or PM/BA professional, if you prefer. I’m sure we could have a lively discussion. I promise to respond personally to every email and to incorporate your thoughts in succeeding articles. You may reach me directly at [email protected].

Robert K. Wysocki, Ph.D., has over 40 years experience as a project management consultant and trainer, information systems manager, systems and management consultant, author, training developer and provider. He has written fourteen books on project management and information systems management. One of his books, Effective Project Management: Traditional, Adaptive, Extreme,3rd Edition, has been a best seller and is recommended by the Project Management Institute for the library of every project manager. He has over 30 publications in professional and trade journals and has made more than 100 presentations at professional and trade conferences and meetings. He has developed more than 20 project management courses and trained over 10,000 project managers.

In the last Business Analyst Times, Bob Wysocki suggested that, in this day and age, the business analyst and the project manager have much in common with major areas of overlap. He pointed out that the skill and competency profiles of the effective BA and the effective PM are virtually identical. He argued that possibly a new role will emerge combining the competency of both. Boy, did that set the fur flying! As a result, we’ve created a dedicated discussion forum for you to participate in. To go there now,

In the last Business Analyst Times, Bob Wysocki suggested that, in this day and age, the business analyst and the project manager have much in common with major areas of overlap. He pointed out that the skill and competency profiles of the effective BA and the effective PM are virtually identical. He argued that possibly a new role will emerge combining the competency of both. Boy, did that set the fur flying! As a result, we’ve created a dedicated discussion forum for you to participate in. To go there now,