Small Projects Drive Me Crazy!

OK, it is not small projects that drive me crazy. It is what I see project teams doing because a project is classified as a “small” project. Teams get the feeling that there is no need for a BA, no need to follow a process, and/or no need to plan. All of these thoughts just because the project has been labeled as a small project! That’s what drives me bonkers. And what happens on most of these projects? Teams struggle, things are missed, and at the end of this small project, teams scramble to finish up. Of course, no project retrospective is done because; well…it was a small project.

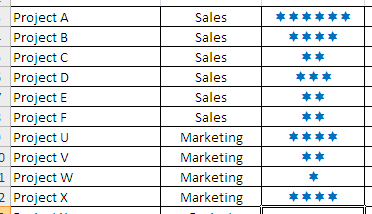

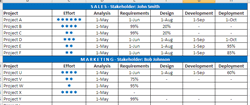

My philosophy is that every project is different, and the team needs to take the steps that add value to the project. This does not mean planning is not important or following a process is not important. It means plan as much as necessary and take the steps in the processes that are needed. You need to analyze each project and determine what makes sense. I know many companies that try to classify projects by size, and then decide if a BA is needed, what techniques to use, how much to document, etc. I have heard people say a small project should have less than 50 pages in a requirements package. So if there are 60 do we no longer classify the project as small? Why try to keep a BA to documenting “x” number of pages? The number of pages should reflect what is needed for that project. The problem with this approach is that projects do not easily fall into buckets. There are too many factors that you need to consider in order to determine what techniques to use, and so on. The type of project, the people on the project, and internal company processes are all high-level factors that need to be considered. Putting projects in buckets opens the team up for failure and focuses the team’s attention on rules in a process. Their attention should be on the customer and the goals of the project.

Teams come up with a process for small projects that are different than large projects because teams try sticking to a prescribed process for every project. Trying to implement every step in a process is overkill for some projects. Coming up with another prescribed process does not solve the problem. In my Going Rogue blog post I think some of you had the impression I do not believe in having a process, or not needing a process as you get more experience. That is not the case. What is true; I don’t believe in a strict prescribed process for everyone and every project. I do believe in a process. It just needs to be fluid and ever-evolving. It has been proven by smarter people than me that having a repeatable process is the key to improvement. A process gives you an anchor to track areas of success and areas for improvement. So, I do believe a process is absolutely necessary.

The only step in a process I can say for sure is needed for every project is planning. For every project the step that must always happen and be taken upfront for a BA is plan the approach for each project. From that plan a determination will be made as to what techniques to use, how much to document, etc. For the techniques chosen, the BA should use the rules or guidelines outlined in the overall process. For example, if use cases are planned to be written for the project, the BA should use the template provided. A BA does not need to complete every step in a process, but if they do perform a step they need to be consistent with the other BAs in the organization.

Projects are not an exact science, so don’t try to place a prescribed process for each and every project. Try to understand the variables of the project, the people, the internal processes, and then plan your approach. I approach projects like I approach my kids. They are each very different, so I treat them in the manner that is best for them. I do not cheer for my oldest daughter at sporting events because she shuts down and stops playing. My son loves when I scream like a raging lunatic at games because he thinks it’s funny. I say it motivates him and he does not want to admit it yet! My youngest daughter, well, I have not figured her out yet!

Happy New Year everyone. I am looking forward to another year of great discussions on the profession we all love!

Kupe

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Jonathan “Kupe” Kupersmith is Director of Client Solutions, B2T Training and has over 12 years of business analysis experience. He has served as the lead Business Analyst and Project Manager on projects in various industries. He serves as a mentor for business analysis professionals and is a Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP) through the IIBA and is BA Certified through B2T Training. Kupe is a connector and has a goal in life to meet everyone! Contact Kupe at [email protected]