Real Reuse for Requirements

A telecommunications company in a hotly competitive market needs to deliver the next generation of cell phone to its customers quickly, and at the lowest possible cost. The company wants to adopt a baseline set of requirements for the next generation project, but must make necessary modifications to leap ahead of the competition.

An automotive supplier must produce embedded software components consistently and reliably for its OEM clients. To do so, the supplier’s development process must account for the slight variations required by each manufacturer.

Requirements reuse provides organizations, like those illustrated in the scenarios above, with the unique ability to share a requirement across projects without absorbing unnecessary duplication of artifacts within a repository. This is a critical capability that accelerates time to market and cuts development costs. Shared requirements can either track to the ongoing change made by the author or they can remain static if the needs of the project dictate. Further, change to a shared requirement can be made by anyone and the system handles the branching and evolution of that requirement appropriately.

The concept of reuse is a familiar notion within the software development realm, but less common when considered in the field of requirements management. There are various definitions and use cases which must be taken into consideration when implementing a solution to address requirements reuse.

This whitepaper discusses the elements that make up a requirement and establishes common understanding of how requirements evolve, how that evolution is retained, and how organizations can reuse requirements to speed business innovation, reduce complexity and control costs.

Dissecting a Requirement

To understand the concept of requirements reuse, we must first look at the various parts of a requirement: data, metadata and relationships.

Data

Describes an object, and is relevant to the object itself. An example of data may be a summary or description of a requirement.

Metadata

This is data about the data, which aids in organizing or using the object within a process. It typically describes the current state of the object, and has the same scope as the data itself. For instance, metadata may describe the State/Stage within a requirement workflow (i.e., Approved, Rejected, Satisfied, and Tested).

Relationships

This characteristic of a requirement allows you to model:

-

structure (i.e., Consists Of, Includes);

-

history (i.e., Revision Of, Derived From);

-

conceptual links or traces (i.e., Satisfies);

-

references (i.e., Defined By, Decomposes To);

-

security (i.e., Authorized By, Enables).

Any given requirement can have information in each of the data, metadata and relationships categories. When requirements are reused, any or all of the information can also be reused.

An organization’s chosen requirements management tool needs to have an underlying architecture and the user capabilities that support the strategic level of reuse dictated by the demands of the organization. Since reuse can occur at a number of different levels by leveraging the data, metadata and relationship elements of a requirement, flexibility is also critical to solving the reuse challenge.

History, Versions and Baselines

When implementing a complex reuse scenario, or even a system where requirements persist release after release, one must be able to identify significant points in that requirement’s evolution. In the development world, these significant points are called “versions.” This term may mean different things to different people, so we will begin with a definition of the term “version” as it applies to requirements reuse and show how it relates to similar terms like history, baselines and milestones.

Consider a system where requirements are captured within requirements documents but are stored as individual items within the repository.

History is the term used to describe the audit trail for an individual item or requirement. All changes made to the item, whether it is to data, metadata or its relationships are captured in its history. History answers to the who, when and what questions with respect to changes to that item.

Version represents a meaningful point in an individual item’s history. Not all changes to an item are significant and warrant a new version of the item. For example, the reassignment of a requirement from Nigel to Julia would not require a specific version identifier. The change is recorded to the item’s history, but a new version is not created.

Baseline is a very similar concept to version but has a much different scope. Individual items are often organized into groups or sets. In the requirements management domain these sets are called documents and a baseline is a meaningful point in a document’s history. Some organizations use a slightly different definition for baseline. Rather than being a snapshot in time for a given document, a baseline, as defined here in the context of requirements reuse, is a goal to work towards. For the purposes of this discussion we will call the goal-oriented baseline a milestone in order to distinguish between the two.

Requirements management claims to allow for the versioning of individual requirements. Many tools support versioning by way of cloning or copying the entire requirement. Even fewer solutions relate the copy to the original requirement.

Although related, versioning and reuse are not the same. The concepts of versioning are often confused with that of reuse. In the next section, we will explore various reuse scenarios to illustrate the differences (and the benefits) of versioning and reuse.

Reuse or Not Reuse? – The Many Flavors of Requirements Reuse

Requirements Reuse without Reuse – Share

The ability to share an item between projects, documents or other work efforts could be considered a form of reuse. Under this definition all of the projects that are sharing the item see, and can possibly even contribute to, the evolution of the item. The metadata on the item is shared as are all the relationships and the data.

This is not real reuse. I question whether to call this reuse at all, but it is included here for completeness.

Requirements Reuse without Heritage – Copy

As mentioned previously, copying an object from one place to another can also be considered a form of reuse. In fact, this is the form of reuse that Microsoft Word (or any other non-Requirements Management tool) supports. When an analyst opens a document, selects some content and performs a copy/paste gesture into another document, they are reusing that content for a new purpose. This form of reuse has no knowledge of heritage or “where did I come from” and of course changes in one document have no impact on changes in the other. In fact, changes are completely independent and one document has no knowledge that change occurred in the other, let alone what the change might have been.

This is also not real reuse. Any flavor of reuse must minimally include a pointer to where the original content came from.

Requirements Reuse with Heritage

Given the above scenarios, let us assume you can answer the “where did I come from” question. Augmenting the copy with the pointer back to its origin provides several options for reuse. It is the manner in which this link is leveraged that will differentiate each of the following reuse models. Most RM tools available today have some notion of links or relationships – if not at the individual requirement level, at the document level. Document level links are better than nothing, but they are not very powerful. In the long run, they don’t really answer the traceability question in sufficient detail to be meaningful.

Having a link to an item’s origin is the start of real reuse though it is certainly not the end.

Requirements Reuse with Change Notification

In this situation, a requirement and all related information (data, metadata and relationships), is reused in its entirety. Project state determines the state of the requirements at the time of reuse, and any change to requirements in a reuse scenario causes a ripple effect, flagging all artifacts related to those requirements as suspect.

Requirements Reuse with Change Control

Reuse with Change Control is similar to Reuse with Change Notification in that data, metadata and relationships are reused in their entirety. This seems, and in fact is, the same as the Share topic discussed above, however, there is one significant difference; the two projects sharing the same requirement only share it until the point in time where one project needs to change it. When the information changes a new version/branch is created and only items referencing that new version are declared suspect. All other projects or documents are unaffected.

Requirements Reuse with Annotations

In the two reuse paradigms above, the requirements and related information (data, metadata, and relationships) are reused in their entirety. In Reuse with Annotations, only some of the information belonging to a requirement is identified as a candidate for sharing and reuse. The rest of the information is specific to the project or document. The shared information is held in the repository while the other information belongs to the project or document reference. Each instance of the requirement being reused has its own metadata and relationships. The project or document state is, or can be, independent of the state of the requirements that are contained within it. New versions of the requirement are automatically created when the shared information in the repository is changed. These changes that trigger new revisions can suspect other references, as well as other items in the system, by the ripple effect of that change. For example, changes to requirements may affect test cases or functional specifications downstream.

Once you have project or document independence in terms of the metadata, you have the ability to model both a dynamic (share) and static (reuse) form of reuse at the same time. The project manager or analyst decides if they want to remain consistent with the evolving requirement in a dynamic way or if they want to lock the requirement down such that the impact of change does not affect their project.

Requirements Reuse with Annotations and Change Management

Applying change and configuration management paradigms onto the requirements management discipline in a single integrated and traceable solution can bring the power of reuse to a new level. By incorporating a process on top of reuse and controlling how and when requirements can be modified and reused enables you to reap these benefits without unnecessarily branching and versioning objects unless it is authorized and appropriate to do so. Requests for Change (RFCs) come in, get filtered and are directed by various review boards. Some of these RFCs get approved and assigned to users to affect the requested changes. Ideally, this change management process can define what types of changes can be made; whether it is modification, branching, applying a baseline or other gestures. Only when an approved RFC is associated with a requirement can an analyst modify the requirement, causing the system to version and branch accordingly, and notifying the related constituents appropriately.

There are clearly, additional reuse models that are not described herein – Component level reuse, documents reuse and various combinations of these with annotations and change management for example. This paper provides only a sampling. The business needs and strategic goals within the group, business unit or business as a whole will help determine which model is most effective for the project or organization.

Is Requirements Reuse Right For Your Organization?

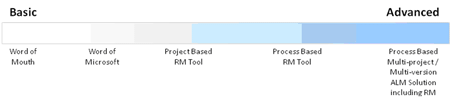

Requirements reuse is not for everyone. There is a broad spectrum of need in terms of requirements management tooling in the market today, and organizations first need to know where they lie on the requirements maturity curve.

1 The requirements maturity curve is not really a curve at all but a measurement of the current process and tools used and/or needed within an organization when it comes to requirements management. As organizations evolve along the curve, the need for more capabilities – such as change management, process and workflow, traceability, reuse, etc. – within their requirements management framework exists.

Many companies are still in the infancy of requirements management. They have not yet adopted a requirements management tool, and are currently using business productivity applications such as Microsoft Word or Microsoft Excel to capture and track requirements. They may look for capabilities such as ease of document import, rich text support, and downstream traceability to ease business adoption. These organizations are not yet at a point of requirements sophistication where reuse support is necessary – or maybe they are but have not found a tool to support their needs.

However, if an organization has progressed on the maturity curve with respect to requirements management, and is managing multiple projects and thousands of requirements in parallel and seeking to reduce complexity, lower cost of development, and shorten innovation cycles, then requirements reuse is a concept that should be investigated.

Let’s face it, regardless of where an organization falls on the curve, reuse in its most basic form will provide a boost to productivity. Rather than re-writing requirements, copy them and modify them for the needs of each project – you will save keystrokes as well as leverage the structure and organization these requirements were managed under in the past. After all, how many different ways can the requirements for logging in to an application be specified really? Ok, likely quite a number, but within any one organization the need to standardize and streamline application access exists and leveraging requirements from one application to another to provide this similar type of functionality can only be a good thing™ (Martha Stewart).

In any case, concentrate on the problem domain before jumping into the question “is requirements reuse right for me?” What challenges is the organization facing in terms of requirements management? Here is a list of sample questions an organization can ask to determine if reuse is a concept that could be leveraged and if it is, which flavor of reuse is best suited to the need.

Doug Akers is a Product Manager at MKS Inc., (www.mks.com) the global application lifecycle management (ALM) technology leader, that enables software engineering and IT organizations to seamlessly manage their worldwide software development activities. through a single enterprise application, resulting in better global collaboration and higher roductivity. MKS supports customers worldwide with offices across North America, Europe and Asia. Doug Akers can be reached at [email protected]