Can I have My Requirements and Test Them Too?

A study by James Martin, An Information Systems Manifesto (ISBN 0134647696) has concluded that 56% of all errors are introduced in the requirements phase and are attributed primarily to poorly written, ambiguous, unclear or missed requirements Requirements-Based Testing (RBT) addresses this issue by validating requirements to clear any ambiguity or identifying gaps. Essentially, under this methodology you initiate test case development before any design or implementation begins.

Requirements-based testing is not a new concept in software engineering – in fact you may know it as requirements driven testing or some other term entirely – and has been indoctrinated in several software engineering methodologies and quality management frameworks. In its basic form, it means to start testing activities early in the life cycle beginning with the requirements and design phase and then integrating them all the way through implementation. The process to combine business users, domain experts, requirements authors and testers; and obtain commitments on validated requirements forms the baseline for all development activities.

The reviewing of test cases by requirements authors and, in some cases, by end users, ensures that you are not only building the right systems (validation) but also building the systems right (verification). As the development process moves along the software development life cycle, the testing activities are then integrated in the design phase. Since the test case restates the requirements in terms of cause and effect, it can be used to validate the design and its capability to meet the requirements. This means any change in requirements, design or test cases must be carefully integrated in the software life cycle.

So what does this mean in terms of your own software development lifecycle or the overarching methodology? Does it mean that you have to throw out your Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) process and adopt RBT? The answer is no!. RBT is not an SDLC methodology but simply a best practice that can be embedded in any methodology. Whether the requirements are captured as use cases, as in Unified Process, or scenarios/user stories, as in Agile development models, the practice of integrating requirements with testing early on helps in creating requirement artifacts that are clear, unambiguous and testable. This not only benefits the testing organization but the entire project team. However, the implementation of RBT is much cleaner in formal waterfall-based or waterfall derived approaches and can be more challenging in less formal ones such as Agile or Iterative-based models. Even in the most extreme of the Agile approaches, such as XP, constant validation of requirements is mandated in the form of ‘customer’ or ‘voice of the customer’ sitting side-by-side with the developers.

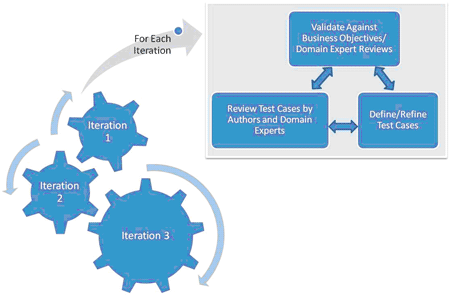

To illustrate this, let us take the case of an iterative development approach where the requirements are sliced and prioritized for implementation in multiple iterations. The high-risk requirements, such as non-functional or architectural requirements, are typically slated in initial iterations. Iterations are like sub-projects within the context of a complete software development project. In order to obtain validated test cases, the team consisting of requirements authors, domain experts and testers cycle through the following three sets of activities.

-

Validate business objectives, perform ambiguity analysis. Requirement-test case mapping.

-

Define and formalize requirements and test cases.

-

Review of test cases by requirements authors and domain experts.

Any feedback or changes are quickly incorporated and requirements are corrected. This process is followed until all requirements and test cases are fully validated.

Simply incorporating core RBT principles into your methodology does not imply that fewer errors will be introduced in the requirements phase. What it will do is catch more errors early on in the development process. You have to supplement any RBT exercise by ensuring you have the means to build integrated and version-controlled requirements and test management repositories. You must also have capabilities to detect, automate and report changes to highly interdependent engineering artifacts. This means proper configuration and change management practices to facilitate timely sharing of this information across teams. For example, if the design changes, the impact of this change must be notified to both the requirements authors and the test teams so that appropriate artifacts are changed and re-validated.

Automating key aspects of RBT also provides the foundation for mining metrics around code and requirements coverage, and can be a leading indicator of the quality of your requirements and test cases. True benefit from the RBT requires a certain level of organizational maturity and automation. The business benefits from having increased software quality and predictable project delivery timelines. Thus, by integrating testing with your requirements and design activities, you can reduce your overall development time and greatly reduce project risk.

Sammy Wahab is an ALM and Process consultant at MKS Inc. helping clients evaluate, automate and optimize application delivery using MKS Integrity. Mr. Wahab has helped organizations with SDLC and ITSM processes and methodologies supporting quality frameworks such as CMMI and ITIL. He has presented Software Process Automation at several industry events including Microsoft Tech-Ed, Java One, PMI, CA-World, SPIN, CIPS, SSTC (DoD). Mr. Wahab has spent over 20 years in technical, consulting and management roles from software developer to Chief Technology Officer with companies including Tenrox, Osellus, American Express, Parsons, Isopia Compro and Iciniti. Mr. Wahab holds a Masters in Business Administration from the University of Western Ontario.

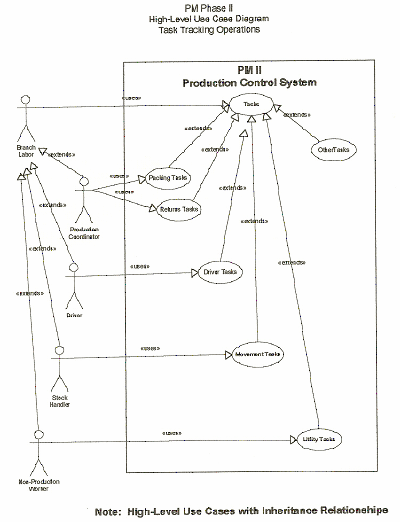

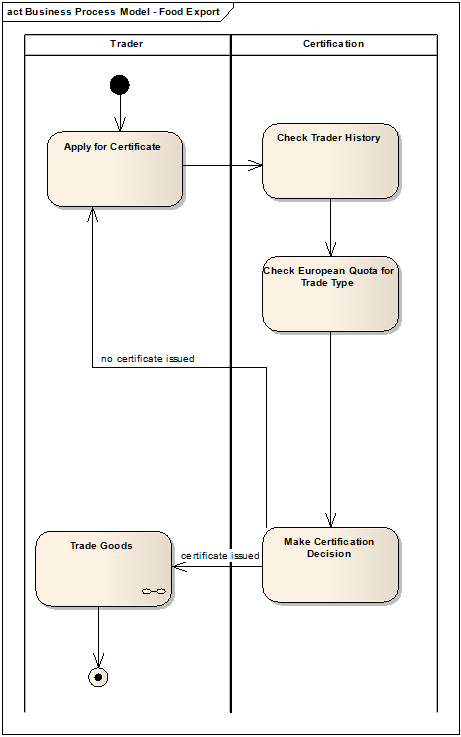

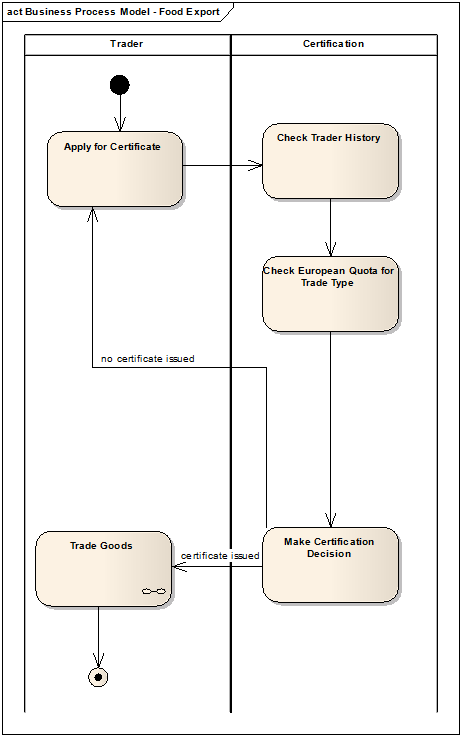

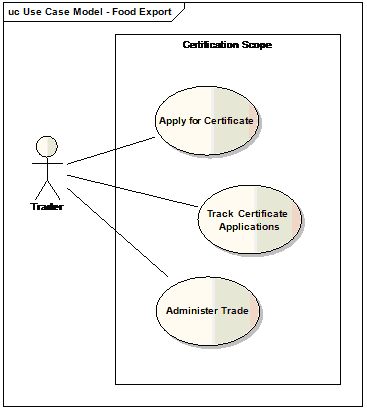

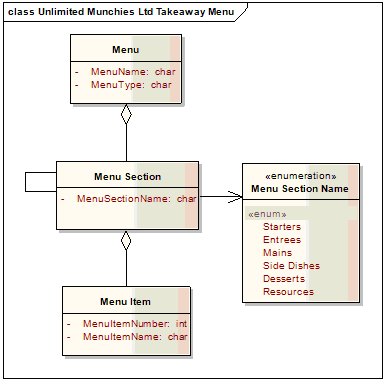

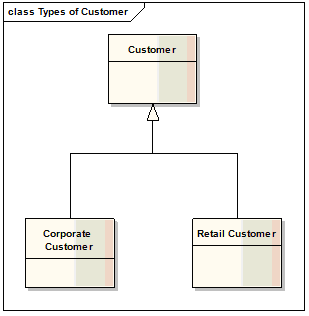

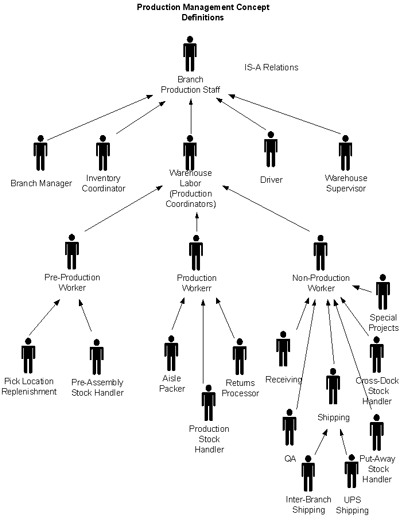

understood by technical and non-technical staff alike. Because staff members are already familiar with their business, they can now better see the complete picture and readily grasp new and advanced concepts such as inheritance (IS-A Relations) in the diagrams.

understood by technical and non-technical staff alike. Because staff members are already familiar with their business, they can now better see the complete picture and readily grasp new and advanced concepts such as inheritance (IS-A Relations) in the diagrams.