Business Process; A Thing of Beauty

The English romantic poet John Keats wrote in the poem Ode on a Grecian Urn ‘”Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” – that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’ This article proposes that, by recognising and reflecting on how a business behaves, we can find, cultivate and hone its beauty by clearly seeing the culture and behaviour that will make that business uniquely successful in its chosen field.

The previous articles in this series looked at seeking out good by setting the scene using a business context model, and at finding the truth within a business by understanding what real things exist and are true at any time of the day, however the business behaves, using a business domain model. This article looks at why we model the dynamics of a business and its people.

Unless we can see how the business behaves, it is very hard to understand it. It is therefore important that we can encapsulate what the business does so that we can refine and streamline its behaviour, reduce unnecessary complexity and focus on purifying its business offering. As an analogy, an athlete will develop a process to maximise performance, eliminating all unnecessary activity. There may be a small measure of uniqueness in the process depending on the physical and mental nature and build of the particular athlete, but most athletes will follow a similar process for their sport.

There are two main camps nowadays when choosing a notation for modelling business process. I like to use the Unified Modelling Language (UML) because my business customers tell me that it is easy to pick up and read and because it covers all the types of business modelling that I require (dynamic and static). The Business Process Modelling Notation (BPMN) covers only business behaviour (both notations are owned and managed by the Object Management Group). In addition, many government bodies and industry groups such as the United Nations, the World Customs Organisation and the Telemanagement Forum set standards and industry patterns using the UML.

There is another faction – those who describe the business without a notation – the textual modellers who have the genuine concern that their business people will not like or understand the standard notation.

I have only ever experienced positive feedback on the notation, willingness and enthusiasm from the business and an immediate understanding of a few simple symbols, but, it is our job to create and communicate understanding, not the notation’s job. The notation is simply a language with a ‘dictionary’ and some ‘grammar’ rules. It is our job to ask all the right questions in the workshop (remembering we should always model with the business), to apply logic to a number of jumbled verbal descriptions of what is going on and to label each model element in a meaningful way in order to communicate the understanding reached. Otherwise the business will not understand the result! It is the combination of analytical skill and of the UML notation which won the following accolade. Recently during a domain modelling session (please see the article “The Importance of Business Domain Modelling“), a fellow business analyst, new to the UML, told me that he had looked down to think about something, then had looked back up at the whiteboard and exclaimed to himself how well the entire discussion had been recorded in a matter of seconds.

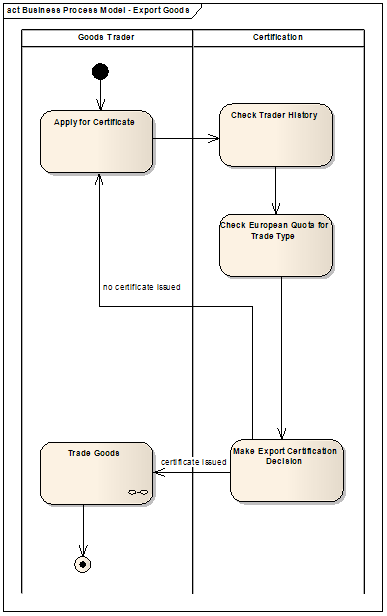

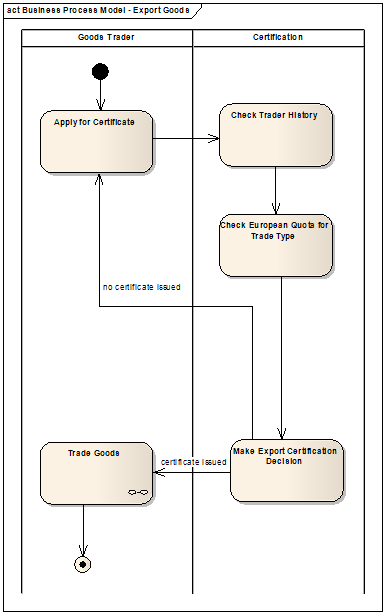

Most business analysts are familiar with modelling the business process at some level. If we can answer the question “what happens next?” then we are dealing with a dynamic view of the world, i.e. depicting the behaviour and activity of the business area of interest. For example, the following (simplified) UML activity model of an outdated UK government business process to do with the international trade of food, specifies the business activity requiring automated support.

Note that a business process always has a starting point, a finishing point and directions on where to go when there are several paths to choose from. These are three of the most frequent review comments I make. Apply rigour and logic! For instance, I can only trade goods if a certificate was issued. Also note that the activity swimlanes (Goods Trader and Certification above) can be derived from the business context model (please see the article “The Business Context Model: As Good as it Gets“) by reusing the actors and business services or areas of interest already identified. The most frequent review comment I make is about the words used to name an activity. Each element in any model must be labelled in a meaningful way. I often see activities labelled like this – “Do Administration” or worse “Enter Data”. These have no meaningful business goal and therefore we cannot hope for good understanding.

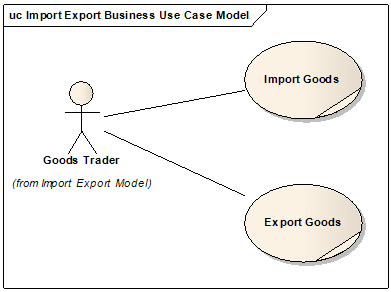

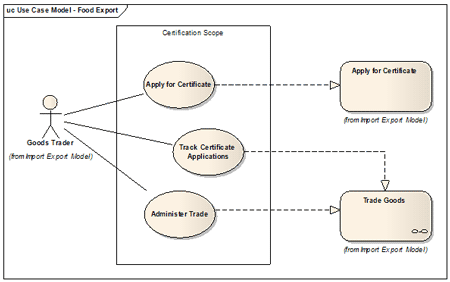

Incidentally, it is useful to model at a higher level as we learn about the business; the business use case model is an ideal way to model disjointed business processes that do not logically flow one to another. For example, in international trade, we might identify the processes that are important to our piece of work in the following way, perhaps including a description (in a good modelling tool of course) before we model each process. They should be named to express an important result of value to the business or a major goal. We could even use the strategic business objective as the business use case name.

A business use case is also a useful container for business policies, business rules and constraints which can later be inherited by any software specified.

While some people think that specifying software requirements is the only aim of a business analyst, my view is that this activity should be regarded as a possible end goal depending on the findings of analysing the business. While the focus of this series is on business analysis, I will diverge a little to help refocus our attention on the business when we do step further into software specification i.e. to specify structured functional software requirements as system use cases (because a use case describes a single interaction between a user and a system that meets a goal of the user). There is misunderstanding about why we have use cases. Briefly, a system use case exists to partially or wholly automate and support a business activity in a business process. Therefore, we should not invent use cases from thin air. They should be derived. I have just read an article giving guidance on how to choose whether to model use cases or business process. I claim that we cannot know which use cases we need without studying the business process they are there to support. Otherwise, it’s like administering medicine without knowing what’s wrong with the patient.

How do we derive use cases? By studying the current behaviour of the business and improving it to a more desired state and then by looking at which activities we can enhance and support further. Please reference the Capability Maturity Model Integration [CMMI] which is an open framework for business process improvement describing five levels of business maturity: Level One is otherwise known as the ‘Beast’, and we might nickname Level Five as ‘Beauty‘. This begs the question – how do we know when we have found a system use case? The answer is when the goals of the business process are understood. What I mean is that we must model goal focused activities and those goals, once recognised, will guide us in informatively naming those activities in Verb + Noun format. When we understand the goal we have a system use case – possibly with the same name. If we don’t understand the goal of an activity, then we must look closer, like we do when showing a bee on a flower to a child – what is the bee doing and why? It may be that the activity identified is too ‘big’ or too ‘small’ and we need to ask many more questions.

Only by deriving use cases from a good logically thought out business activity model can we be sure that our software requirements analysis will be fit for purpose. How else would we know? By writing down the wish list of our business people, hoping that everyone can remember exactly what they said in the requirements meetings so that the 300 pages of free text that resulted are not subject to an endless round of revision? In addition, praying that the statements made can act, in a timely manner, as an accurate specification that really does meet the subset of business goals and objectives assigned to the piece of work from the overall business strategy?

Many business process modellers like to model in ‘layers’ and I am often asked how many layers one should model and what level of detail is required at each level. Some industry standards also model in layers, such as the Telemanagement Forum’s eTOM business process model. My preference is not to layer the business process, because I want the model to be public and exposed, say on my business owner’s wall, and I want the model to be useful as a focus for meetings and discussions. This means that it must fit on one page if printed! I have often seen four walls completely covered by a single layer process, or layers upon layers of business process never used again after the model is “completed” – incidentally the model can never be completed in my book. It is really a judgement for each modeller to make depending on their piece of work, but I prefer a single layer with exceptions modelled on further pages so that I can keep the main process on one page (“main” = what happens most of the time with exception activities shown to indicate when something goes wrong). This may mean that I must keep the goal of each activity quite ‘big’.

Of course, the best businesses are never complacent, always proactively striving for enduring beauty: measuring and optimising business objectives and activities; and visualising the business economics (cost, revenue, benefits). Therefore a model of the business process can never be complete – it is a snapshot of an ever evolving set of activities.

With a smoother running process, we can focus our attention on what really counts – the value chain; designing and pricing products and services. It can be a painful realisation when we know we must actively go looking for inefficiencies in our daily business life. After all, beauty is pain, so the saying goes.