Start your visual facilitation journey with letters.

With the growing use of agile practices and design thinking, there is also a growing awareness of the importance of working visually.

Written by Line Karkov on . Posted in Articles.

With the growing use of agile practices and design thinking, there is also a growing awareness of the importance of working visually.

Written by Kristen Gandier on . Posted in Articles. 2 Comments on Breaking Through the Stakeholder Surface

The Stakeholder Blueprint

Stakeholders are an important component of the business ecosystem, and especially important to initiatives, as they include any individual person or group that has any sort of connection to the business need or change at hand. Stakeholders can have a straight-forward connection to the initiative, or be a more complex and challenging piece. Stakeholders are not always the person or group with the easiest road of access, and overcoming challenges and barriers with stakeholders can build trust and facilitate meaningful business relationships and engagement.

Speaking the language of stakeholders is about understanding not only what is obviously promoted and agreed, but also about listening to what is not said. Within stakeholder silence can be hesitation, but it could also be unspoken agreement and support, or even untapped input. Not all stakeholders speak the same language, and it may depend on the initiative and accompanying environment. Understanding environment is important, as well as having self awareness to ensure no assumptions are made on perception of stakeholders.

Everyone knows the phrase, “watch out for those quiet ones”. In the landscape of stakeholders, it is not always a reliable approach to accept the loud voices of support as loyal, and the quiet ones as adversity. Understanding different communication needs can help to elicit not only requirements, but important business information to help with the initiative. This means not only thinking, but also performing and prioritizing outside of the box.

The Unlikely Mentor

Within stakeholder groups, there could be many different types of business relationships. Mentors can come in all shapes and at all career milestones. You may have spent some time focusing on one particular area of your organizational structure to find a mentor, only to happen upon your best ambassador and catalyst of growth from an unexpected network connection.

Mentoring as a professional input has changed over the years, and no longer is represented by the one-dimensional approach of an employee with seasoned expertise providing wisdom to a junior, within a specific organizational facet. Mentoring can be from one or many blended sources, allowing the optimal blend of experience, perspectives and advice to inspire multi-directionally. It is no longer the formal, stuffy documented professional connection and more modernly exists in a fluid, dynamic environment that fits more to the organic professional environment and multiple avenues of existing career paths.

Cohesion and the Business Need

Mapping stakeholder personas is an important Business Analysis technique in identifying specific sources, decisions and choices for involvement to the initiative. Keeping touchpoints open and approaches objective helps to elicit valuable information for projects and maintain a team’s engagement and value.

When leading teams through initiatives and keeping communication central, there may be times when information is not always easy to unpack. Depending on the initiative, challenging group conversations about outcomes may come up time-to-time, such as the sometimes “unpopular” outcomes of:

These outcomes can divide stakeholders, make some nervous, and may even inspire a reaction to perceived setbacks, even if they are indeed the best options. With the right communication though, these may actually allow for important reconfigurations for stakeholders to find a new perspective. That environment of honesty and trust can directly impact another future initiative, or even exist in understanding business needs, and how something such as “doing nothing” may prevent loss from continuing to pursue an initiative that delivers low-value.

Keeping stakeholders informed and direction honest can:

When the team has the same view, the road to travel there is easier.

Written by Christina Lovelock on . Posted in Articles.

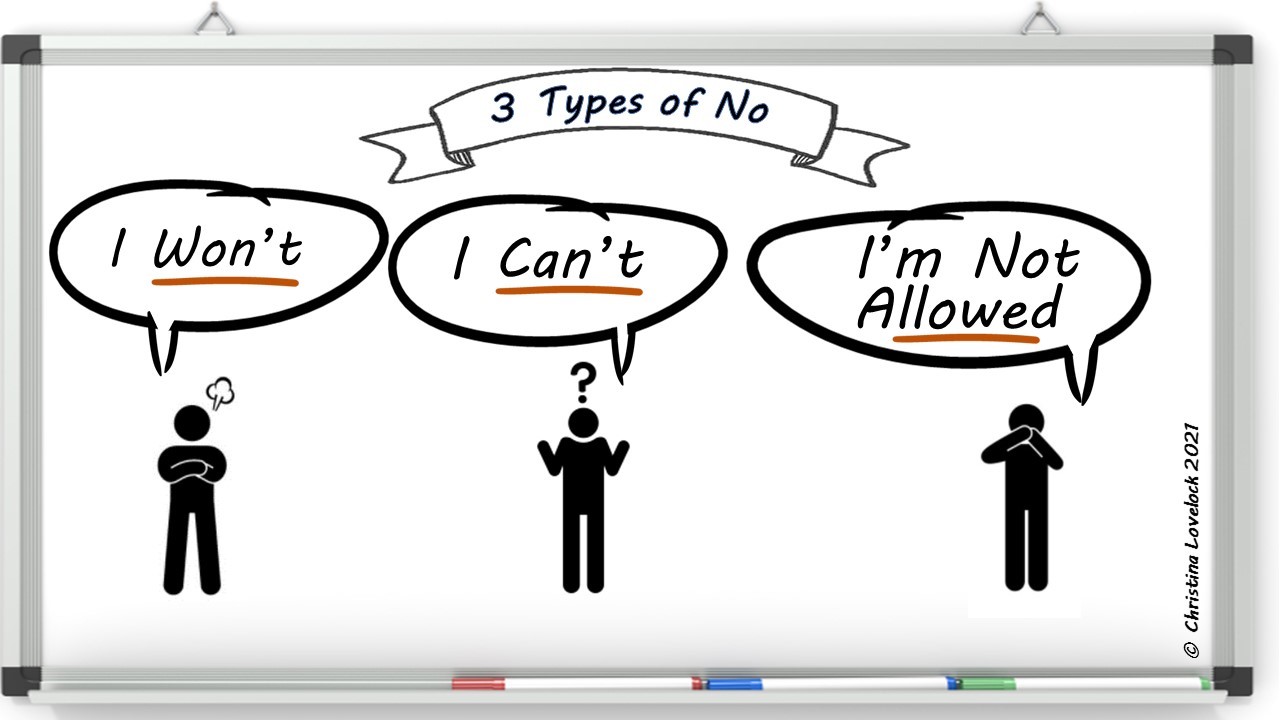

People say ‘no’ to us all the time. This can seem very final, a total unwillingness to engage.

Understanding which type of ‘no’ we are hearing can help us to avoid labelling people as ‘resistant to change’, and promote more effective engagement.

Resistant To Change

Change professionals can forget how hard it is to change. Organisations enter into seemingly un-ending change programmes, restructures and transformations. For those whose job is not part of this change industry, all of these well-intentioned initiatives feel like a distraction from ‘real’ business objectives and personal goals. So, as change professionals, we hear ‘no’ a lot. It comes it lots of forms such as “No one is able to attend that workshop”, “It is not possible to release anyone for the project team” and “We’re too busy”.

It is not possible to conduct business analysis or achieve any kind of change without other people. We need their input, we need to ask questions, we need them to engage. When they are unwilling, we can be quick to label them as ‘resistant to change’.

The Three Types Of ‘No’

People often avoid actually saying no, and they certainly avoid giving their real reasons and motivation for doing so.

I Can’t

This usually comes down to either capability or capacity. I can’t help you because:

This can be a helpful type of no, because it may reveal incorrect assumptions or the lack of knowledge or resources. It may also provide sign-posting to the best-next-step or person who does have what is needed. If there is willingness to help, but practical issues make it a ‘no’… this can be useful too. Creating a conversation which adds “yet” to the and of all the above statements changes the narrative. It becomes a discussion about planning: obtaining funds or resources, scheduling work, obtaining information.

I’m Not Allowed

There may be real or perceived barriers to saying yes – in the form of ‘permission’ concerns.

This can include:

These types of restriction may be real – in which they can be investigated and challenged to understand if they are still relevant or a product of historic decisions, assumptions and preconceptions. If they are perceived limitations, they can also be explored and challenged. Again, if there is a willingness to help many of these blockers can be overcome, the first hurdle is to identify them!

I Won’t

The trickiest type of no is one which is underpinned by unwillingness to help. This can be fuelled by issues such as:

Control is a major factor in whether we enjoy our work or not. People sometimes refuse to engage in one area as a reaction to a lack of control in another. Change initiatives often see education about the change as the way to overcome resistance. “Sell the benefits!”, “Explain what’s in it for them!”…

Listening rather than telling may be the best way forward from an “I won’t”. Be genuinely curious, try to see their perspective and try to address concerns and barriers. Not everyone will be convinced or motivated to be involved. Decided how much time and energy can by spent on one person.

One ‘No’ Disguised As Another

The most socially acceptable and ubiquitous type of no is “I am too busy”. This is an “I can’t” statement. When we reframe this as a question of priority as opposed to time, it can help to move the conversation forward – however “too busy” maybe a stalling tactic, where the underlying no is really: I won’t.

If attempts at tacking the question of priority, and addressing potential scheduling options do not work, then the underlying cause is not really time. Handling this honestly and openly, looking for the common ground or areas of potential compromise may help. If all else fails consider escalating appropriately, but this should not be the first thought.

Conclusion

For people to say “yes” to our many requests for input and engagement they need three things: capability, capacity and motivation.

Appropriate and proactive training and development, planning, and communication clearly have significant roles to play in ensuring these three things are in place. However, at a human and day to day level, we can all try to understand the “no” we are hearing, and work with that person professionally and compassionately to achieve the best outcomes for our organisations.

Written by Christina Lovelock on . Posted in Articles.

Obviously No One Says EXACTLY What They Are Thinking All Of The Time, But Why Do We Hold Back What We Believe To Be Valuable Contributions? In The World Of Remote Working, It Is Important To Understand This Issue.

In this context, it’s when we make a decision not to put forward our idea, question, opinion, objection or point of view. In same-room meetings, it was easy to see when someone’s body language changed, or when someone began to look confused, thoughtful or hesitant. Good meeting-chairs, and good colleagues, would pick up on this and invite the contribution. In video calls it is much more difficult to pick on these cues, so many contributions are being missed.

BAs need to be aware of self-censoring from two perspectives 1) our stakeholders may not provide the information or insight we need from them 2) we may be stopping ourselves form contributing due to a variety of underlying causes.

Here are some of the reasons people hold back.Here are some of the reasons people hold back.

Many of us prefer to maintain the outward illusion of a harmonious team than face some of the more difficult questions. Unfortunately the disharmony will spill out in other ways, impacting relationships and productivity. To further extend this metaphor – checking that everyone knows where we are headed and is rowing in the same direction is not the same as ‘rocking the boat’!

If someone makes a very confident statement we believe to be wrong or disagree with, it’s difficult to voice another idea if we feel uncertain. Some people sound very confident all of the time, and leave no room for alternative interpretation or doubt. This can leave others feeling “there’s no point arguing with them”. This is not a positive outcome for organisations. Research shows that when people are “100% certain” of something, they are only right about 85% of the time.

When we don’t really care about the topic or issue, its more likely we will hold back. Sometimes a topic feels off track, unnecessarily detailed or covering old ground. Particularly in long meetings, or towards the end of meetings, people have mentally moved on and we are unlikely to making the best quality contribution.

If we find ourselves consistently uninterested in the outcome of discussion, perhaps it’s time to look for a new room and a new discussion.

Many of us avoid conflict, because it feels uncomfortable. We worry that relationships may deteriorate or be affected. We need to invest in relationships to create the trust required to constructively disagree, the security to express dissenting views. We also fear endless debate, and may feel unwilling to prolong the discussion further! People also worry about looking foolish or deliberately uncooperative. Fear is a major factor in self-censorship.

When everyone else stays silent, it is easy to assume they all agree. When we believe we are the only one ‘out on a limb’/ ‘willing to stick their head above the parapet’ (whichever analogy is more prevalent in your organisation) we are less will in to speak our minds.

The most innovative and productive teams have competing ideas and multiple perspectives.

Good facilitation

Online meetings need different facilitation skills to face-to-face meetings. Getting the best contribution from every participant, keeping everyone engaged and not simply seeking quick-agreement are essential. The ability to exchange questioning glances or clarify positions on the way into a meeting have been reduced – we must make it easier for people to speak when they have a different point of view.

Inviting a minority opinion with phrases such as “Is there another way of looking at this?”, “What could we be missing here?” and “Let’s hear from some who is not totally convinced” make it much more acceptable to voice dissent than questions which don’t really invite further contribution such as “So, are we all in agreement?”.

Also consider:

It is useful to reflect on our contribution with questions such as:

Create a culture of reflection by posing some of these questions at the end of a session.

As business analysts, we need to understand this issue, as it has the potential to significantly affect our work. Being alert to self-censorship means we can encourage participation and ensure we don’t miss out on an important contribution from others, and we can question our own motivations when we choose to stay silent.

Written by Kathleen O'Brien & Cassandra Jackson on . Posted in Articles.

Is there a hidden pitfall in your business analysis efforts?

Could unconscious bias be reducing your effectiveness as a business analyst? Consider a meeting when someone from a different cultural background is quiet throughout the meeting. We can easily favor more talkative participants and overlook the individual’s contributions in the process.

Unconscious bias, also referred to as hidden or implicit bias, is an unconscious preference for, or against, a person or group. This bias differs from explicit bias which is an obvious or blatant prejudice held at a conscious level. Unconscious bias comes in many flavors and may be based on a person’s background, physical attributes or even a person’s name.

Biases are a biological survival mechanism that drives our patterns of thinking. The ability to categorize people quickly and automatically is a built-in survival mechanism that helped early humans to distinguish friend or foe. In our modern world, these biases may lead to detrimental behaviors such as prejudice or injustice. In fact, biases thought to be extinguished remain as “mental residue” in most of us. Studies show people can be consciously committed to an ideal and deliberately work to behave without prejudice but still possess unconscious biases which may lead to stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.

Unconscious bias, if not addressed, may lead to unintended consequences for individuals, teams, and the strategic mission of the organization. If an interview panel demonstrates gender bias for males in leadership roles, it is possible the most qualified individual will be denied the career opportunity. A lack of team productivity can result when a manager selects an inexperienced project manager simply because both individuals attended or graduated from the same university. If the marketing organization misses a segment of the population in their strategies, the market share for a new product or service can be lost to competitors or impact the strategic organizational mission to reach all populations. We must continuously strive to guard against biases that lead to inequities.

Despite these risks, biases may serve a purpose. Some biases are formulated from myriad sets of experiences that allow us to understand a situation in ways that foster diversity of thought and contribute to the effectiveness of the team.

Why are we calling unconscious bias a hidden pitfall when applied to the practice of business analysis? Business Analysis is the practice of eliciting information from diverse stakeholders to get the best set of business needs, requirements, decisions, and outcomes. Unconscious bias can prevent a business analyst from achieving this goal.

The Business Analysis Book of Knowledge (BABOK) Version 3 states the following as important underlying competencies for professionals involved in the discipline of business analysis:

These underlying competencies enable a Business Analyst to effectively relate, cooperate and communicate with different kinds of stakeholders, including executives, sponsors, colleagues, team members, developers, vendors, learning and development professionals, end users, customers, and Subject Matter Experts (SMEs). A Business Analyst possessing these underlying competencies is uniquely positioned to address unconscious bias, and ultimately improve the team’s ability to get the best set of business needs, requirements, decisions, and outcomes.

Successful Business Analysts demonstrate Communication Skills through listening and diplomacy. Consider this example when a female colleague presents a probable solution to the company’s desire to expand in another international market. She is ignored by the meeting facilitator. Within minutes, another male colleague presents the same version of his solution. The facilitator quickly acknowledges and praises the male colleague’s proposed solution. After a quick observation, the Business Analyst tactfully interjects, acknowledges the original idea from the female, and the additional information from the male colleague. In this instance, the Business Analyst demonstrates Behavioral Characteristics of adaptability and trustworthiness through diplomatic skills that address the unconscious bias.

When exercising Interaction Skills, the Business Analyst can establish trustworthy connections that allow an understanding of the stakeholder’s goals, feelings, likes, dislikes, fears, and uncover unconscious biases that exist and can impair effectiveness. During a stakeholder interview, a key stakeholder makes a derogatory comment regarding a colleague’s upcoming cultural celebration. The Business Analyst does not immediately respond to the comment but makes a deliberate decision to pair the two in an upcoming roleplay in which the key stakeholder interviews the colleague regarding customer perceptions of their product.

In addition to demonstrating the above-mentioned competencies, the Business Analyst has a collection of techniques to minimize and overcome the hidden pitfalls of unconscious bias. Here are a few ideas:

Combating the hidden pitfalls of unconscious bias will require relentless and on-going efforts over time. As we seek to expose personal or team biases, Business Analysts can become change agents for environments where employees feel valued, and innovation flourishes and thereby leads to increased profitability and productivity for the corporation.

References:

https://www.tolerance.org/professional-development/test-yourself-for-hidden-bias

https://builtin.com/diversity-inclusion/unconscious-bias-examples

(2015) Underlying Competencies In A Guide to the Business Analysis Book of Knowledge (Version 3.0 pp 188-210). Toronto, Ontario. Canada.

Get Access to Live and On-Demand Webinars, Templates, Claim PDU/CDUs, and Many More!